In the tech world where measurement and being “data-driven” are fundamental to product development processes, research functions must speak the language of replicable findings and scale. This earns researchers respect for being “scientific” and able to fit in with the worldview of product folks, engineers, and data scientists. Here, research plays the function of informing by giving teams confidence in their directions.

But I want to highlight a function that is arguably just as important, and that’s the role of research to inspire, not just inform.

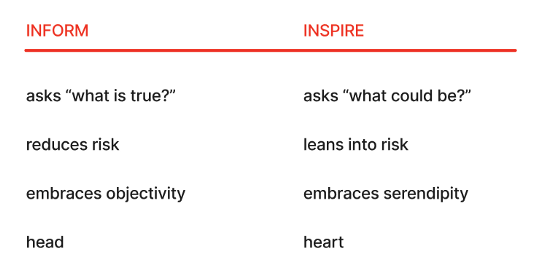

While informing answers “what is true?”, inspiring pushes the boundaries of “what could be”.

Informing helps teams reduce risks when making an important decision. Inspiring kindles peoples’ creativity and gives them permission to explore, to lean into risks.

Informing embraces objectivity. Inspiring embraces serendipity.

We inform through the head; we inspire through the heart.

When research inspires, it invites people to tap into their endless well of curiosity, promotes divergence of ideas, and gives them permission to listen to their hunches. These aren’t just luxuries; these are pre-requisites for design innovation.

Research that informs merely needs to deliver insights, often in the form of a written report (and sometimes with creative share-outs and storytelling). These insights come in the form of “Here are the factors of X’, “Here are the 5 types of users”, “Here are the pain points of Y”, “Here are the top reasons people do Z”. Research that inspires must deliver an experience to their stakeholders; it’s this experience that becomes a vehicle for inspiration.

When a product team only familiar with the inform function of research gets a taste of inspire, it can feel disorienting. It invites them to dive into ambiguity and peer outside the straight lines they’ve drawn. But this disorienting feeling is the very thing that unlocks creative thinking.

So here’s a provocation that I’ve brought into my research practice when developing my research roadmap:

How might research inspire our product teams?

This provocation assumes that creativity is valuable, that it needs a context to nurture it, and that researchers are not only given permission to facilitate that context, but we should embrace that responsibility.

So how do researchers design experiences that inspire? I’ll share a few suggestions of what’s worked for me.

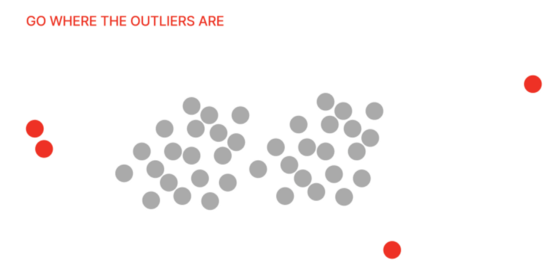

Tactic 1: Research the extremes

To get inspired, we need to look outside the “general” sample, and recruit participants at the extremes or outliers of a group. These folks will provide a unique perspective, perhaps a nascent point of view, that you won’t find when studying the more general population. Have conversations with people who are early adopters, or off the beaten path, or participate in an analogous context. They will provide a contrast to the rest of your research participants that helps the team make sense of the meaning of ‘normal’ and what informs their widely held beliefs. The extremes will also demonstrate something the rest haven’t thought of — a unique use case, a creative strategy, a complex combination of tools — that provokes the team to question the boundaries of the context of study and inspire new ideas.

For example, one of my colleagues was researching the topic of content creators and monetization; where did he go to find extremes? Porn stars — people who had fanatic followers and an excellent grasp of audience engagement. What might they know about monetizing a fanbase?

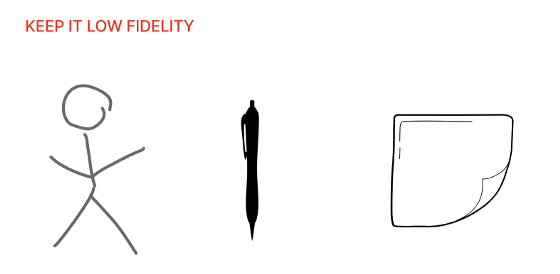

Tactic 2: Explore concepts, then throw them away

Low fidelity concepts are a great tool for facilitating generative conversations. Here, I’m not referring to concept “testing” or “validation”; I mean exploration, where the goal is to have conversations that invite people to turn off their logical thinking for a moment, and be in a space where they can suspend disbelief. The lower fidelity the concepts, the better. Think: simple hand drawn sketches, storyboarding a scene, playing with metaphors. Use these concepts as probes to get people to open up to an idea; or better yet, facilitate a co-creation exercise or have people generate a few ideas of their own.

There’s an art to facilitating these experiences to get people in a generative mindset (a topic for another time), but when done well, the research participants and your team will be rewarded with a newfound energy about possibilities they hadn’t conceived of previously. Suddenly, the constraints of the business and realities of today are put aside, and imagination trumps confidence and certainty.

For example, I once facilitated a 2-hour workshop with 4 participants (along with my designer and product manager). The first hour together was spent building rapport, and building confidence so that these participants felt like experts and were unafraid to be “wrong”. This primed them for our main event: in the second hour, they were invited to explore ideas of what an ideal future user experience might look like. While they vocalized these ideas out loud, my design partner was illustrating in real-time for all of us to see. This helped the participants get visual feedback of their ideas, through another person’s interpretation. Seeing the sketch gave them new ideas of what to build upon, or in some cases, led them to clarify their emerging idea into a concept. There were no right or wrong designs; just a bunch of design directions and reflections about these users’ greater desires. We were all groping around the invisible boundary of what was possible.

Tactic 3: Design an experience your stakeholders will never forget

Sometimes we encounter the researcher that works in her own silo; she goes away to gather data, then synthesizes the chaos quietly through some invisible process, and comes back an expert with a list of insights and recommendations for the team. The researcher has built a wall separating the process from the audience, cutting them off from a valuable learning experience. Instead, the researcher can shift their role; no longer an expert, she can view herself as an experience designer, tour guide, or facilitator.

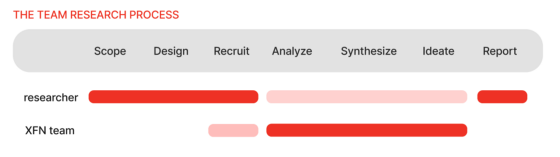

One of the most effective tactics for stakeholder engagement is to invite them into the research process and give them roles and responsibilities to uphold. Have them participate in the data gathering, storytelling, and synthesis… and believe they can do it. This promotes a spirit of adventure, collaboration, and collective curiosity that can amplify the speed and quantity of ideation like no other.

Facilitating such a process is easier said than done; it requires careful and extensive planning ahead of time to set proper expectations, define where the researcher gives up control and where they keep it close, and designing the scaffolds and tools that help the cross-functional team feel excited rather than anxious about the task ahead. You’d be surprised how people can feel self-conscious about their ability to “ask unbiased questions” and “have unbiased interpretations” along with how people are compelled to participate in shared experiences that bring adventure and curiosity.

For example, I once designed a diary study where I recruited 12 participants to try out a new prototype over two weeks. I simultaneously designed a stakeholder “mission”. My team — consisting of product managers, designers, engineers, data analysts, etc. — were each assigned 2 participants that they were to advocate for. Over the course of one week, they were to analyze the raw qualitative data, summarize takeaways, storytell the most resonant user stories to the broader team, and then zoom out and identify themes. I had never seen research (with this volume of data) conducted so quickly, with this level of engagement, and leading to immediate tactical shifts to our product roadmap. It was made possible because every one was given responsibilities and they were trusted to do the job. (This trust was key, and I explain how I designed this team sense-making process and gave up control here).

These are just a few examples to inspire your practice. There are so many other methods: specific tactics of storytelling, field research immersion activities, designing physical location into debrief processes, and many more.

Cautionary note

Beware of over-indexing on inspire and forgetting the job of informing. Often, start-ups lean too heavily on inspire, not realizing that the “research” lacks in rigor and insight (I was guilty of this early in my research career), whereas larger “data-driven” tech companies can lean too heavily on inform, not realizing that new product innovation requires some degree of playing at the edges and getting out of our heads. Ideally, research teams must do the informing so that they can carve out space and permission to do the inspiring. It takes a very seasoned research leader to understand the differences between the two and know when it’s appropriate to apply each (or both) for the particular team dynamics and problem at hand.

Special thanks to Pilar Strutin-Belinoff, Shoshana Holtzblatt, and Altay Sendil for showing me the important role of inspiration in research practice.

Leave a comment